| 29 | More about Pure Functions |

We

’ve seen how to make lists and arrays with

Table. There

’s also a way to do it using pure functions

—with

Array.

Generate a 10-element array with an abstract function f:

Use a pure function to generate a list of the first 10 squares:

Table can give the same result, though you have to introduce the variable

n:

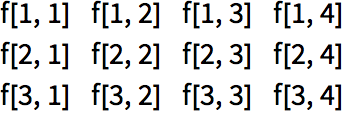

Array[f,4] makes a single list of 4 elements.

Array[f,{3,4}] makes a 3

×4 array.

Make a list of length 3, each of whose elements is a list of length 4:

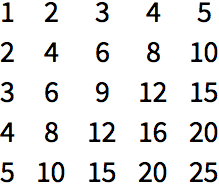

If the function is

Times,

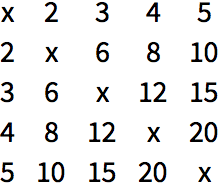

Array makes a multiplication table:

What if we want to use a pure function in place of

Times? When we compute

Times[3,4], we say that

Times is applied to two

arguments. (In

Times[3,4,5],

Times is applied to three arguments, etc.) In a pure function,

#1 represents the first argument,

#2 the second argument and so on.

#1 represents the first argument,

#2 the second argument:

#1 always picks out the first argument, and #2 the second argument:

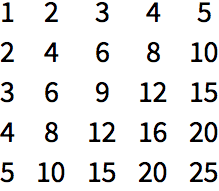

Now we can use

#1 and

#2 inside a function in

Array.

Use a pure function to make a multiplication table:

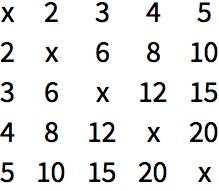

Use a different pure function that puts in x whenever the numbers are equal:

Here

’s the equivalent computation with

Table:

Now that we

’ve discussed pure functions with more than one argument, we

’re in a position to talk about

FoldList. You can think of

FoldList as a 2-argument generalization of

NestList.

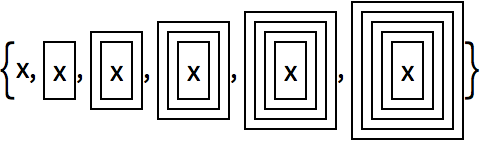

NestList takes a single function, say

f, and successively nests it:

It

’s easier to understand when the function we use is

Framed:

NestList just keeps on applying a function to whatever result it got before.

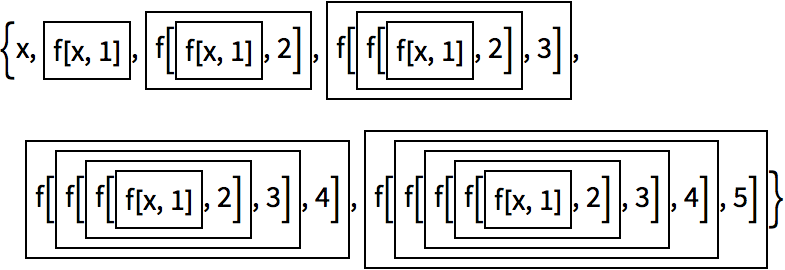

FoldList does the same, except that it also

“folds in

” a new element each time.

Here

’s

FoldList with an abstract function

f:

Including

Framed makes it a little easier to see what

’s going on:

At first, this may look complicated and obscure, and it might seem hard to imagine how it could be useful. But actually, it’s very useful, and surprisingly common in real programs.

FoldList is good for progressively accumulating things. Let

’s start with a simple case: progressively adding up numbers.

At each step

FoldList folds in another element (

#2), adding it to the result so far (

#1):

Here’s the computation it’s doing:

Or equivalently:

It may be easier to see what

’s going on with symbols:

Of course, this case is simple enough that you don’t actually need a pure function:

A classic use of

FoldList is to successively

“fold in

” digits to reconstruct a number from its list of digits.

Successively construct a number from its digits, starting the folding process with its first digit:

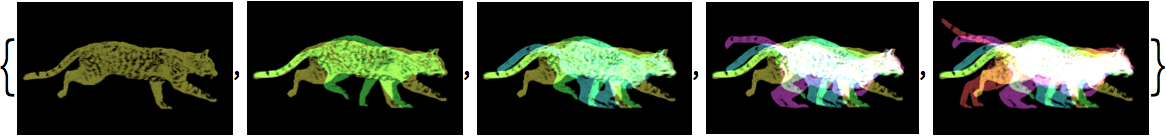

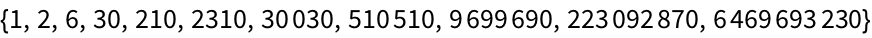

Finally, let

’s use

FoldList to

“fold in

” progressive images from a list, at each point adding them with

ImageAdd to the image obtained so far.

Progressively

“fold in

” images from a list, combining them with

ImageAdd:

The concept of

FoldList is not at first the easiest to understand. But when you

’ve got it, you

’ve learned an extremely powerful

functional programming technique that

’s an example of the kind of elegant abstraction possible in the Wolfram Language.

| Array[f,n] | | make an array by applying a function |

| Array[f,{m,n}] | | make an array in 2D |

| FoldList[f,x,list] | | successively apply a function, folding in elements of a list |

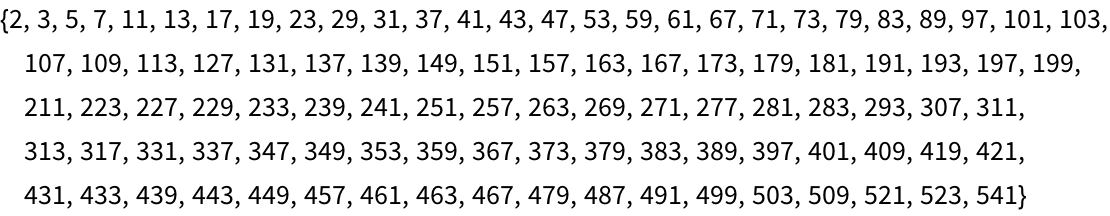

29.1Use

Prime and

Array to generate a list of the first 100 primes.

»

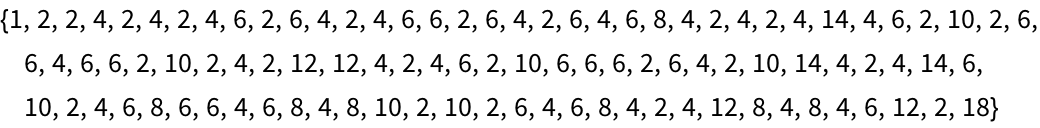

29.2Use

Prime and

Array to find successive differences between the first 100 primes.

»

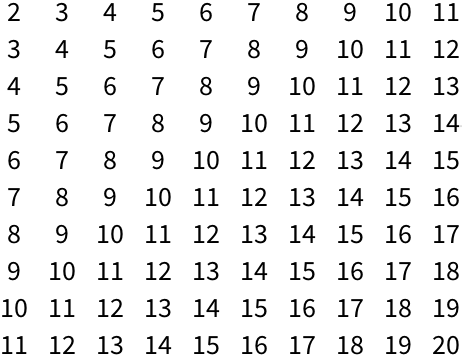

29.3Use

Array and

Grid to make a 10 by 10 addition table.

»

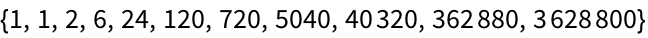

29.4Use

FoldList,

Times and

Range to successively multiply numbers up to 10 (making factorials).

»

29.5Use

FoldList and

Array to compute the successive products of the first 10 primes.

»

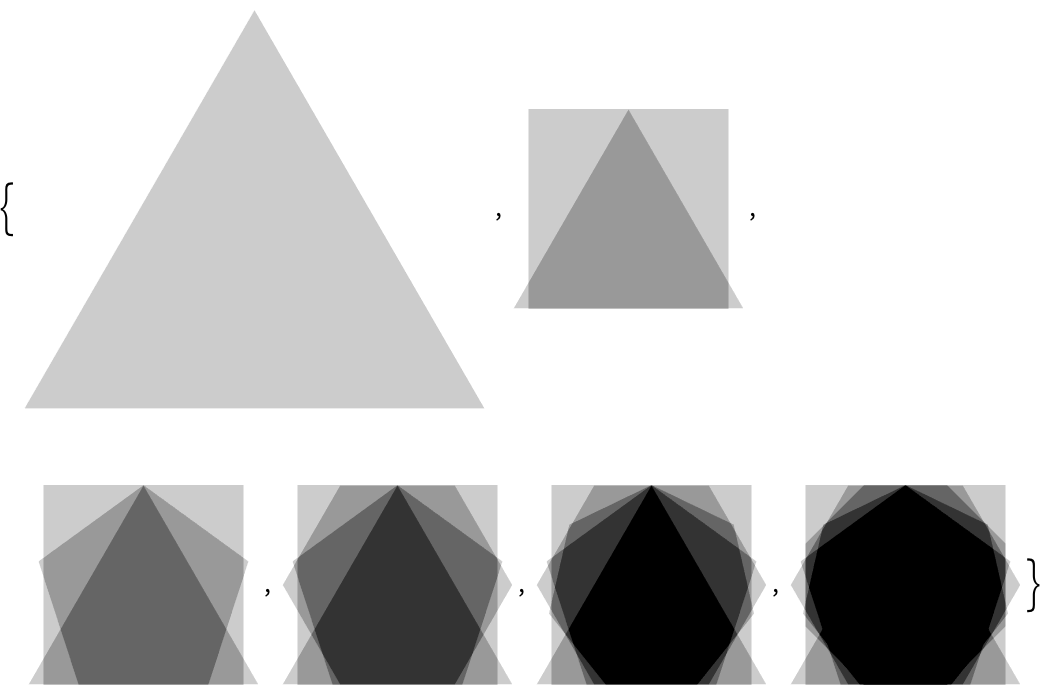

29.6Use

FoldList to successively

ImageAdd regular polygons with between 3 and 8 sides, and with opacity 0.2.

»

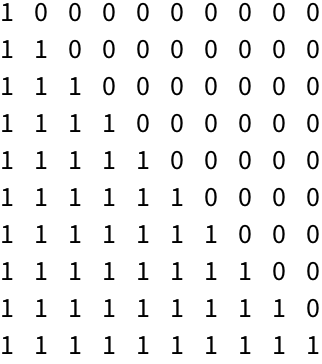

+29.1Use

Array to make a 10 by 10 grid where the leading diagonal and everything below it is 1 and the rest is 0.

»

It

’s equivalent to

#1—a slot to be filled from the first argument of a function.

Either

“slot 1

” (reflecting its role in a pure function), or

“hash 1

” (reflecting how it

’s written

—the

“#” is usually called

“hash

”).

Can one name arguments to a pure function?

Yes. It

’s done with

Function[{x, y}, x+y], etc. It

’s sometimes nice to do this for code readability, and it

’s sometimes necessary when pure functions are nested.

Can

Array make more deeply nested structures?

Yes—as deep as you want. Lists of lists of lists... for any number of levels.

What is functional programming?

It

’s programming where everything is based on evaluating functions and combinations of functions. It

’s actually the only style of programming we

’ve seen so far in this book. In

Section 38 we

’ll see

procedural programming, which is about going through a procedure and progressively changing values of variables.

- Fold gives the last element of FoldList, just like Nest gives the last element of NestList.

- FromDigits reconstructs numbers from lists of digits, effectively doing what we used FoldList for above.

- Accumulate[list] is FoldList[Plus, list].

- Array and FoldList, like NestList, are examples of what are called higher-order functions, that take functions as input. (In mathematics, they’re also known as functionals or functors.)

- You can set up pure functions that take any number of arguments at a time using ##, etc.

- You can animate lists of images using ListAnimate, and show the images stacked in 3D using Image3D.